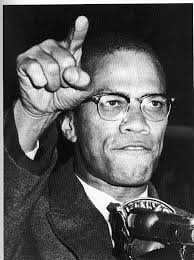

This past week, while people all over the country commemorated the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., I had to revisit The Autobiography of Malcolm X for a class reading. I could not help but think that each year on February 21st, the assassination of Malcolm X goes relatively unacknowledged by this nation. The question that naturally arises is why is this the case? Put more precisely, the question is why is King celebrated as a national hero while X is typically relegated to the footnotes of America’s historical consciousness? One can point to many factors in an attempt to answer this question. However, for the sake of being as brief and precise as possible, attention will be given to one of these factors – namely, Malcolm and the Nation of Islam’s insistence on calling white people devils.

This claim commonly associated with early Malcolm X (during his years in the Nation of Islam) comes from the Myth of Yacub. The myth states that 6,000 years ago on the island of Patmos, Yacub, the big-head scientist created white people in a lab to be a race of devils. He accomplished this feat by genetically modifying the cells of blacks, the original people of earth created by God. By isolating recessive genes in skin cells, genes that result in people having lighter skin, Yacub disrupted the natural order God had established. He knew that as his created race became increasingly pale skin over several generations, they would be more prone to evil and wickedness. When the blue-eyed blond-haired race of devils integrated into society with the original (black) people of the earth, they brought havoc and chaos with them everywhere they went. In order to save the society, black people banished the white race to the mountains of Europe. The rest, as they say, is “history.”

There are several major problems with espousing this myth. Yet before one criticizes it, it is important to note why the myth has been significant for many black people and why certain themes that emerge out of it will always be important. The myth of Yacub represents a faithful attempt by black people to assign meaning and purpose to their lives on their own terms – over and against white domination. This myth can properly be categorized as faithful since it is an example of humanity in its finite reality being grasped by an infinite passion. In various religious traditions, God has become the fundamental symbol for this infinite passion. God represents the transcendent ultimate reality which is dually present at the center of all reality. Mythology, which is often the primary tool of religious expression uses additional symbols to speak with and speak about the ultimate reality. The use and the reliance on symbols are necessary, since God, though always present at the center of all reality, eternally alludes humanity as the transcendent reality. Being faithful to a particular religious tradition has absolutely nothing to do with believing in the historicity or scientific accuracy of the tradition’s mythology. What matters is whether the myths and symbols of a tradition are capable of infinitely grasping one in their finitude and pointing them towards that which is ultimate.

Turning attention to points of criticism, it must be said that religious expressions are overstepping their bounds and are failing to fulfill its unique purpose when it makes claims about science and history motivated by religious convictions.[1] People of faith typically make this mistake when they take their symbols and myths literally. In the case of (early) X and the Nation of Islam, if the myth of Yacub is interpreted as literal scientific and historical fact, the resulting conclusions are completely absurd. The myth in the literal sense makes several unsubstantiated claims about biology, anthropology, and the origins of race and ethnicity. Religiously speaking, the myth is flawed since it presents a symbol of the ultimate reality that does not affirm the humanity of all people. This is why no religious expression should ever label people as devils or demons – it denies that the ultimate reality is present in their finite reality. Stated plainly, the myth asserts that the image of God is not present in all people – this is religious heresy.

In various religious traditions, the devil, and demons have served as mythological and literary symbols for the many destructive forces always present within finite reality. Early Malcolm X and others that subscribe to the myth of Yacub are unquestionably wrong for asserting that white people were created to be a race of devils. However, an honest assessment of western civilization reveals that few forces have been more destructive in the modern world than the concept of whiteness.[2] Thus, religiously speaking, it is not an extreme claim to assert that whiteness is demonic. Whiteness as a concept is so much deeper than certain people having fair and lighter skin tones. When people talk about whiteness as an idea, it typically refers to the modern assumption which states that Anglo-Saxon peoples and cultures are superior to all other peoples and cultures. Additionally, whiteness states that Anglo-Saxon ideals should serve as the objective standard by which everything else is evaluated. Anything that is incapable of adjusting or assimilating to this standard must be destroyed. This idea of whiteness has been at the center of almost every large-scale human catastrophe in the modern world, including colonialism around the globe, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the American Civil War, the Jim and Jane Crow American South, WWII, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the War on Terror, etc. At this point in history, religiously speaking, to not understand whiteness as a demonic force may be negligent and irresponsible.

Malcolm X understood this religious truth. Though he rightfully condemned the myth of Yacub as heresy in his later years, he acknowledged that the idea of whiteness is very much a demonic force. He spoke about this religious truth courageously and unabashedly every chance he got. It goes without saying that the content and the delivery of his rhetoric made the collective consciousness of America very uncomfortable. This is one reason among many as to why King is generally regarded as a great American hero and X is typically ignored or dismissed as a rabble-rouser.[3] But if we are truly interested in building a more just and equitable world for all people – we have to be made uncomfortable, precisely, since we have become too comfortable within an unjust world. Paying specific attention to issues of racism in America, white people have to be made uncomfortable. American society being comfortable in its whiteness is how we have ended up in our current predicament. If white people are genuinely interested in doing things to combat racism, I suggest you start by listening to people, doing things, and being in spaces that make you uncomfortable. If you are white and comfortable while addressing racism, you probably are not doing it right.

[1] Too often in conversations about religion, we incorrectly speak about “faith” and “belief” as if they are the same thing. I have already established faith as humanity in its finite reality being grasped by an infinite passion, which in turn turns us towards the ultimate reality. Beliefs are opinions we believe to be true which may or may not actually be true. We arrive at different beliefs based on varying levels of evidence or lack of evidence. The above statement should not be interpreted as an endorsement of a “blind belief” committed to the claims scholars make about historicity and/or science. It most certainly should not be interpreted as “having faith” in the contemporary methods of science and historicity. The methods of modern science and history, if executed properly, are constantly asking questions of itself, reevaluating itself, and adjusting its claims based on the presentation of new evidence. These kinds of questions should always be encouraged and welcomed as a way to sharpen the disciplines. However, these progressive questions should never be motivated by religious people seeking to bolster or defend the validity of their symbols and myths, especially since the validity of religious expression is not dependent on scientific accuracy or historicity. Making such arguments are not scientific, precisely, since it is arguing from a perspective that has a preconceived non-negotiable conclusion in mind. Arguing such things is theology. And frankly, it is poorly constructed theology for attempting to fit one’s expressions of infinite passion into the finite limitations of contemporary scientific and historical methods – limitations that will likely be overcome in future generations. I am not suggesting that people have faith in science or use science as an expression of religious faith. I am saying that in the modern situation, we should place preliminary belief in the scientific method to tell us about what can be learned about the physical world.

[2] Faithful religious expressions, since they are examples of humanity its finitude being grasped by an infinite passion, emerge out of unique historical, social, and cultural context. Thus, the distinctiveness of religious expressions are often informed by its historical context – that is what I am exercising here. I am not using religious convictions to argue for or against certain historical claims.

[3] It should be noted that towards the end of his life, the content of King’s rhetoric also began to make America collective very uncomfortable. This aspect of his legacy is relatively ignored in contemporary civic celebrations.

Suggested Reading List of Works that Informed this Piece (List is not exhaustive)

Battalora, Jacqueline M. Birth of a White Nation: The Invention of White People and Its Relevance Today. Houston, TX: Strategic Book Publishing, 2013.

Bultmann, Rudolf. New Testament and Mythology and Other Basic Writings. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1989.

Cone, James H. God of the Oppressed. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2000.

Cone, James H. Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare?Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2012.

Cone, James H. A Black Theology of Liberation. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2013.

Douglas, Kelly Brown. Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2015.

Ford, David F. The Modern Theologians: An Introduction to Christian Theology in the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 2001.

Jennings, Willie James. Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Long, Charles H. Significations: Signs, Symbols, and Images in the Interpretation of Religion. Aurora, CO: Davies Group, 1999.

Marable, Manning. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. New York, NY: Viking, 2011.

Tillich, Paul. Systematic Theology. Vol. 1 – Reason and Revelation, Being and God. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press, 1951.

Tillich, Paul. Systematic Theology. Vol. 2 – Existence and the Christ. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Tillich, Paul. Biblical Religion and the Search for Ultimate Reality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Tillich, Paul. Dynamics of Faith. New York: HarperOne, 2009.

Tillich, Paul. The Courage to Be. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

X, Malcolm, and Alex Haley. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Ishi Press International, 2015.